Let's Remember Some Guys

Growing up, chasing dreams, losing friends. It's what we do.

Subscribe here to Calling Balls and Strikes!

High school’s not a period of my life that inspires fond memories.

Mostly, I remember trying to “get” girls and avoid fights with bullies and thugs of various demographics (often failing at both). There were also the interminable weekend nights, loitering in parking lots and vacant fields. If it was cold, I was more than likely to be found drinking beers and inhaling disgusting amounts of second-hand cigarette smoke inside a running car with an overstuffed clique of bored suburban kids. (High school—best days of your life!)

I recall sneaking trips into “the city” any time I could find someone who was willing to drive (or, at least, drive to the Metro-North train station in Tarrytown). And I most definitely recollect being bored to tears in class, so mentally adrift that I could barely hear the lecture. (This part did, however, come with an upside—as inspiration to explore the world through books and culture on my own time.)

But more than anything, I will always associate high school with an unbearable sense of loneliness.

I was socially awkward—both too loud and too meek, overbearing and insecure. I also liked some sort-of-weird but definitely-uncool stuff, and was frequently self-conscious about having divergent tastes.

While I could enjoy plenty of the pop art fed to my generation, I was much more interested in movies and music that weren’t normie af. And this was during an era of pre-internet ubiquity, and way before social media was even a gleam in Mark Zuckerberg’s eye. For as destructive as social media has proven to be for young people, if you were a weird-ish kid in the 90s it was a lot harder to find kindred spirits than it is now.

There weren’t a lot of yoots I knew who were openly interested in politics and history, as I was. Few of my high school cohort held aspirations to not find themselves hanging out in a parking lot on the weekend. And even though we grew up in a time when Channel 5 ran Kung Fu movies on Saturday afternoons and every non-Blockbuster video store had a decent selection of Akira Kurosawa classics, indie navel-gazers, early Woody Allen comedies, and various 1970s “exploitation” popcorn flicks—not too many teens I knew would happily join me in such screenings.

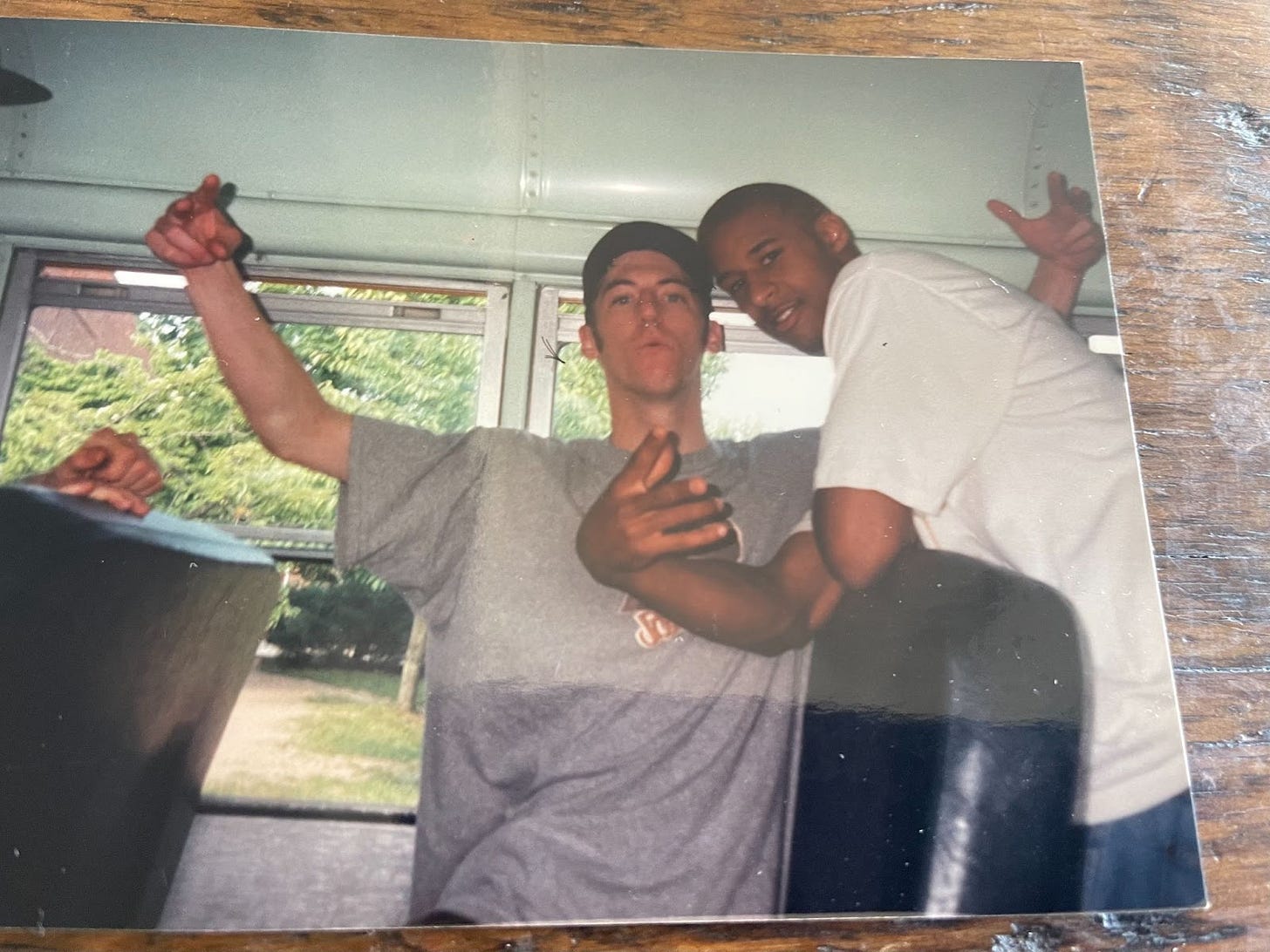

But Dave Lipkin was one of those guys who would. So was Kien Grant.

We were all insufferable, immature, arrogant teenagers. But unlike myself at that age, those two guys at least outwardly appeared comfortable in their own skins—not seeming to give a fuck who thought they were cool (although I’m sure they did at times, they were just more adept at concealing it).

Dave was a skateboarder, not too interested in school, who at various points frequented the NYC punk and hardcore scenes (the most elitist of counter-culture teenage cliques). He could be a real prick, zeroing-in on your deepest insecurities and exploiting them for a cruel laugh. But he could also be a good friend, fiercely loyal, and generous.

Kien was more studious, played on our high school’s basketball team, eschewed drugs and other forms of garbage living—and was a constant source of charm and humor. (It was Kien who convinced one of our teachers that he needed to be excused because he suffered an injury while “freestyle walking.”)

At that age, I wasn’t sure what I was supposed to look like or who I should hang out with. Indeed, I tried on every persona I thought could get me laid—from grunge to metalhead to guido. (As it turns out, the wounded, self-effacing, and sardonically charming “John Cusack” schtick turned out to be the most successful, but not until college.)

Those guys and me weren’t “best friends,” but we didn’t need to be. We each shared a restlessness about where we lived and where we wanted to go. As different as we were, and as often as we’d fight about stupid shit, there was a respect and admiration among us. We saw each other as authentic—an uncommon attribute in a ticky-tack suburb at any point in the late 20th century.

We didn’t always hang, but when we did—we could hang.

They were a couple of the dudes whose occasional company helped me hold on until I got to college—where I surmised it wouldn’t be too weird to be interested in books, politics, and “old” things.

When we came of age, I went my way, and they went theirs. I never fully lost touch with either of them, but you know, life marches on.

All the Time in the World Is All You Get

We lost Dave in November 2006, the victim of a hit-and-run driver who struck him while he was skateboarding in Los Angeles.

When I saw Kien at Dave’s funeral, we embraced without a word. Neither of us had any.

Later that day, I told Kien I was proud of him (which I now realize is not something I say to friends often). But I meant it—he was already chasing his dreams without apology, like he always said he would.

We lost Kien this past weekend. Reports are thin, but it appears he was shot twice at his home in Mexico, the victim of a botched robbery.

I’m sitting here in Queens, sadly sipping an adult beverage, once again trying to find the words.

Dave died too young to achieve his dream of making a pretentious indie film (he loved Harmony Korine’s movies, I did not—which was always a sore point between us).

But Kien was, for a time, an actual rock star. He was Netic Rebel, a name he’d adopt in private life, as well.

In the 2000s and early 2010s, “Netic” fronted Game Rebellion—a Brooklyn-based, politically conscious rap-rock band, sometimes likened (if not compared) to Rage Against the Machine and Public Enemy.

They were big in the Afro-Punk scene (such as it was), which had a lot of crossover appeal to impassioned music heads of various other niche genres. Game Rebellion’s Searching For Rick Rubin collaboration mixtape with J.PERIOD holds up more than a decade later. (Seriously, bookmark the link and listen later).

Netic/Kien and company toured, performed on bills with legends (Bad Brains! Mos Def!), and even had a video on MTV during the last days the network actually played music. As the band’s days wound down, Kien never stopped dreaming or doing it his way.

He was an outspoken vegan, art-lover, activist, and entrepreneur. For a time, he co-owned a Brooklyn coffee shop along with his brother, former NFL running back Ryan Grant. And he was jacked—he was always so goddamned jacked.

Though I hadn’t seen Kien in years, we kept in touch, always planning to meet up, often sharing potential opportunities we thought would be good for each other—and, of course, taking any opportunity to make fun of the herbs. (He got a particular kick out of my 2016 interview with Black Lives Matter leader DeRay McKesson, who Kien told me was “baby soft.”)

Learning the news that he’s gone, and that he went under such violent and unimaginable circumstances…it’s been tough to accept. (Physiologically, it almost resembles a concussion—blurry vision, a dull ache behind the eyes, and some difficulty maintaining balance.)

This isn’t news to those that know me, but I’ve lost a lot of friends. To suicide. To overdoses. To war. To car accidents. To mental illness. And once again now, to murder. I used to obsess over what it means, all these tragedies, all these young men gone. (I even made a movie loosely based on some of these experiences.) But I came to recognize it was a form of masochism, from which nothing good came.

In large part through a discipline of therapy and meditation, I’ve largely accepted it doesn’t mean anything. It’s not about me. People live, people die. You know some of them, you love some of them, you will lose them all—eventually.

Jim Carroll—the New York City-based poet who was played by Leonardo DiCaprio in The Basketball Diaries—for a time had his own punk group, The Jim Carroll Band. Their 1980 record, Catholic Boy remains to me one of the most re-listenable of its era.

The unquestioned highlight is a song called, “People Who Died,” which given its content and my own history would on the surface appear to be the kind of thing I ought to avoid.

Mary took a dry dive from a hotel room

Bobby hung himself from a cell in the tombs

Judy jumped in front of a subway train

Eddie got slit in the jugular vein

And Eddie, I miss you more than all the others

This song is for you my brother

Those are people who died, died

They were all my friends, and they died

There’s a bunch of reasons “People Who Died” doesn’t upset me, but rather, uplifts.

It’s a catchy three-chord pop tune cloaked in NYC punk attitude. It’s darkly ironic without being self-pitying. And it’s a reminder that some of us will bury more people at a young age than others. But we’ll live, love, and lose again—because what else are you gonna do?

When I hear “People Who Died,” I feel less alone.

If Dave were around, he’d probably call me corny as hell for writing any of this at all. Kien would probably laugh at Dave’s ballbusting, but then compliment my taste in DJing for the bereaved.

I’m sad they’re gone, and sadder still about the ways they went. My heart breaks for their families and loved ones. I’m glad I knew them.

They were both my friends, they just died.

Anthony,

This is a beautiful bit about two iconoclasts who I always respected and even envied for the very characteristics you point out. And whether you knew it or not, a lot of people in HS did think you were cool in a way we all knew would age better than the way other people were considered cool.

Anthony- you were totally cool in high school! Hope you are doing well old friend. Your writing is awesome and very touching.