"Maus" Should Be Read By Everyone, Including Eighth Graders.

The graphic novel's "removal" by a small town school district isn't a "banning," but neither is it a "manufactured outrage."

(WARNING: This post contains plot spoilers for the three-decade-old book Maus, which if you haven’t read already, you should.)

The McMinn County (Tennessee) school board in January voted to remove Maus from its eighth-grade English curriculum. For a seemingly minor change in a small town school system, it caused a bit of a stir.

McMinn is home to about 54,000 people—of whom 75% identify as religious Christians—and went 79%-19% for Trump in the 2020 election. Its school board decided in a 10-1 vote that using Maus as teaching material was inappropriate for eighth graders—not because it teaches about the Holocaust, but rather, because of the book’s depictions of nudity, profanity, and graphic violence.

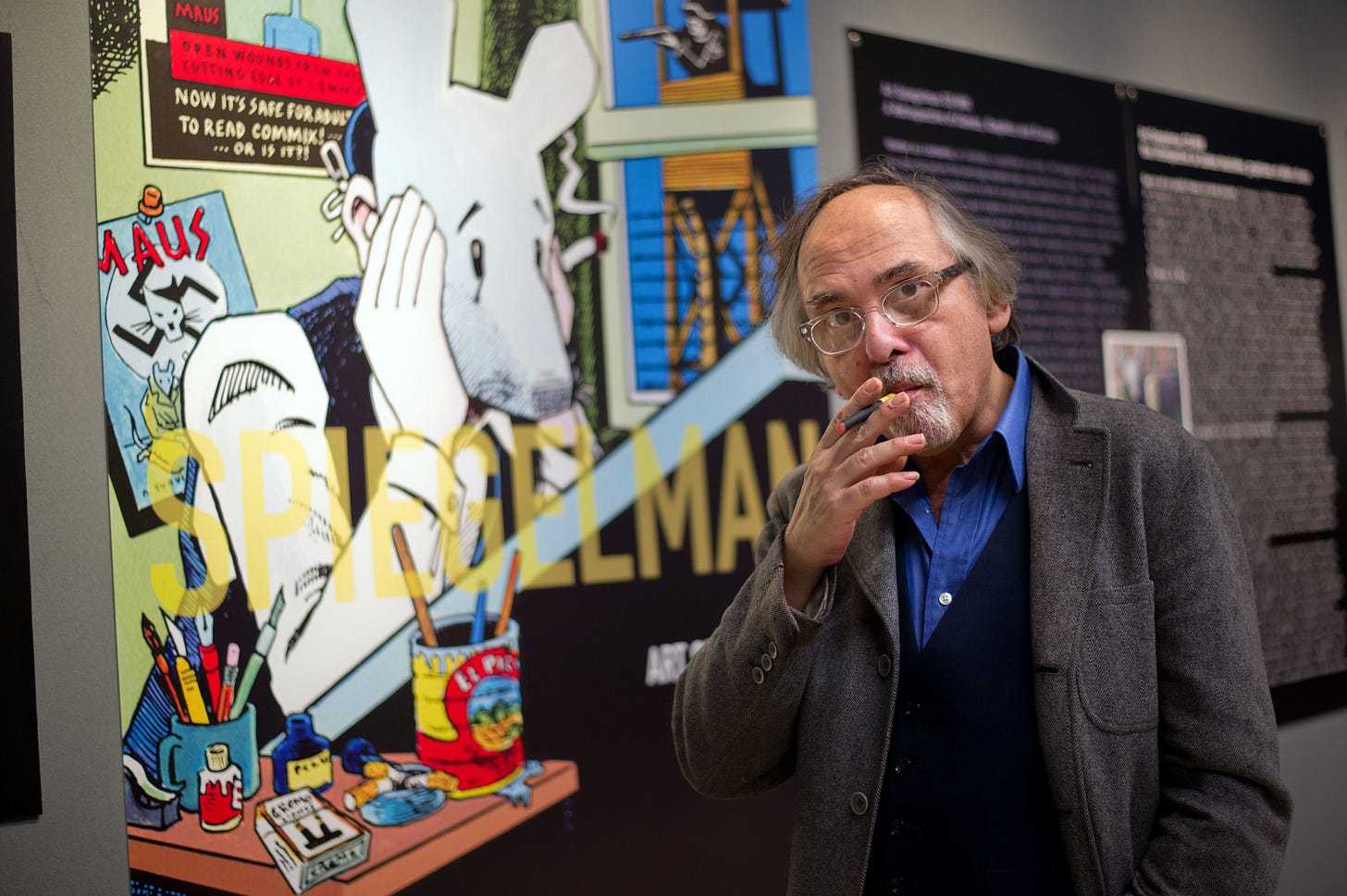

Maus is a graphic novel by Art Spiegelman, originally serialized over a decade but ultimately released as a singular (well, two-volume) graphic novel in 1991. It won the Pulitzer Prize in 1992. It is, to date, the only graphic novel to ever win the Pulitzer Prize.

The book’s removal in a single school district was hyped as a “banning” by many mainstream outlets, mocked as hypocritical conservative snowflakery by some on the left, and blithely dismissed as a “manufactured outrage” and “fake news” by at least a few voices on the right.

It is, in fact, a small deal that’s part of a much bigger deal—because it illustrates a timeless conundrum regarding free expression and public education. That is, who gets to decide what books are “problematic” and which students are entitled to a “safe space”?

(In much-less publicized local school board news, a more progressive-leaning district in Washington state voted last week to remove To Kill a Mockingbird from its curriculum, in part because of its use racial epithets and its “white savior complex." Conservative culture warriors noticed, but that’s about it.)

The inner workings of small-town school boards don’t always provide fodder for national news, but during a political moment when angry parents are tipping elections over school-related issues, it seems obvious why this case would generate outsized attention—as well as bad faith interpretations by some critics on the left and overly-generous apologetics on the right.

Maus is an incredibly raw, harrowing, and beautiful autobiographical story driven by the author’s father recounting his life, beginning as a successful young Jewish businessman in Poland—with a wife and child—to a conscripted soldier in the Polish Army fighting the Nazis at the onset of World War II, then as a prisoner of war, and later, a prisoner of the ghetto, and later still, a survivor of the Nazi death camp at Auschwitz.

The narrative bounces around in time, as the father recounts the story to his son—a cartoonist named Art Spiegelman. (The first volume is subtitled, “My Father Bleeds History.”)

Beyond just the innumerable, unspeakable horrors of the Holocaust—including the creeping terror of watching civilization disappear around you—there is betrayal, trauma, survivor’s guilt, and even dry humor experienced through the mundanity of everyday life. All the Jewish characters are depicted as anthropomorphic mice, while the Nazis are cats, with other identities denoted as various animal species.

Maus also deals with the author’s mother’s suicide years two decades after the war, as well as his older brother’s death—slain as a toddler in a mercy-killing by the woman who had been protecting him and several others, before she killed herself and her charges rather than allowing any of them to be taken to a concentration camp.

It’s unbelievably emotional, wrenching stuff. If you read it, you’d never forget it. That’s what great art is supposed to do. That’s why it’s effective.

The fact that it’s a graphic novel—essentially a literary comic book—makes it accessible to people (especially young people) who might not otherwise have the interest or attention span to read a dense novel or history book. That makes it a perfect tool with which to teach eighth-graders—typically age 13 or 14—about the Holocaust.

There is no reason to believe, based on the publicly available school board minutes, that removing Maus from the curriculum was born of antisemitism or Holocaust denial. It’s much simpler than that. It’s old-fashioned socially conservative prudery.

That said, none of the McMinn school board’s objections to having young teenagers read Maus make much sense, in factual terms.

This past weekend, I picked the first Maus book off my shelf to double-check that my memory hadn’t deceived me. (It hadn’t: there is almost no nudity or profanity, and very little graphic violence in Maus.)

In the 159-page book, the first bit of disturbing imagery is on page 32, when Spiegelman’s mouse-father, in 1938, sees a Nazi flag flying in a Czechoslovakia town square. The next bit of arguably disturbing imagery is on page 47, when Spiegelman’s mouse-father is depicted firing a rifle at German soldiers on the Polish border at the start of World War II.

On page 83, four mouse-men are depicted hanging in public, executed by the occupying Nazis for selling unauthorized goods to fellow Jews. This image, in particular, was cited in the McMinn County school board meeting’s minutes as a prime reason the book should be removed.

Yes, these are disturbing images, but there is nothing excessive about any of these images. They are, in fact, incredibly tame considering their historical context.

But the real sticking point for McMinn County parents was the “sexual imagery” in Maus—which for the life of me I could not find on repeated readings.

“We don’t need this stuff to teach kids history,” said one McMinn County parent. “We can teach them history and we can teach them graphic history. We can tell them exactly what happened, but we don’t need all the nakedness and all the other stuff.”

At issue, apparently, is a single frame where Spiegelman’s mother is depicted naked, and dead by suicide, in a bathtub. Her image is mostly obscured, and a single pencil-drawn dot indicates a nipple on a female breast. That’s the extent of the “nakedness” in the first book of Maus.

Another McMinn County parent cited Spiegelman’s past work as a cartoonist for Playboy (which was non-pornographic, and which took place in the 1970s and 1980s), as a disqualifying factor.

“You can look at his history, and we’re letting him do graphics in books for students in elementary school,” the objecting parent said. “If I had a child in the eighth grade, this ain’t happening. If I had to move him out and homeschool him or put him somewhere else, this is not happening.”

Also deemed objectionable was the single use of the word “bitch,” which appears in Maus as one of the many tormenting thoughts in the author’s head following his mother’s suicide. (Among the other thoughts are “Mommy!”, “Hitler Did It!”, and “Menopausal Depression.”)

Some on the left seized upon this story and tried to frame it as part of the right-wing “critical race theory” furor—a truly lamentable, illiberal backlash to “wokeness” which has led to dozens of misbegotten proposed (and in some cases, enacted) state laws banning the teaching of “divisive concepts” in public schools.

But the Maus affair is much more mundane.

My take, to the extent I can distill it into a few sentences:

This is, indeed, a “cancel culture” story, in the sense that parents and activists have been banning, censoring or de-platforming books for stupid reasons since time immemorial—quite often because of depictions of sexuality.

And, no, censorship doesn’t just mean “by the government”—as the movie industry can attest via the Hays Code, the red-scare blacklist, and its current self-imposed ban on unflattering depictions of the Chinese Communist Party.

The censoring of Maus in McMinn County isn’t part of a national right-wing campaign to keep kids from learning about the horrors of history, it could have happened in any number of small, highly-religious communities at any point in the past century.

But it is not, as some on the right have argued, a “manufactured outrage.”

To cite (but not single out) just one example, The Hill’s YouTube show, The Rising, did a segment on the de-Mausification of McMinn County titled: “Manufactured OUTRAGE?” Co-host Robby Soave (an editor at Reason and a former colleague of mine) began the segment by correcting the record: Maus had not been banned, but merely removed from the curriculum.

This is true, just as it was in 2020 when an Alaska school district removed several American classics, including The Great Gatsby, from its curriculum. The difference is Soave referred to that particular book-shuffle as a banning, and added that it was a “textbook example of progressive goals…inadvertently being cited as a reason to thwart progress.” So, kind of an outrage.

The segment’s other co-host, Batya Ungar-Sargon (deputy opinion editor for Newsweek and the author of the book, Bad News: How Woke Media is Undermining Democracy) correctly praised the book as an important and affecting work of art, but also said McMinn County parents had good reason to object to Maus being taught to their 13 and 14 year-olds. She added that the book is “filled” with nudity and profanity and disturbing visuals (as I previously noted, it is not)—and that there are better books with which to teach teenagers about the Holocaust.

Both hosts agreed that Nobel Peace Prize winner Elie Weisel’s Holocaust memoir, Night— first published in English in 1960—was a much more appropriate choice for an eighth grade curriculum than Maus.

But in terms of depicting the horrors of Auschwitz, Night is arguably even more graphic than Maus.

Weisel vividly describes the smells of death emanating from the crematoriums, the agony of death marches, and the horrors of children watching their parents slowly die. The only appreciable difference between the two tomes is one book has pencil-drawn pictures of anthropomorphic animals and the other does not.

Moreover, Night has been regularly challenged by parents of eighth graders who also feel that there are “better books”—ones less likely to inflict discomfort—with which to teach middle-schoolers about the Holocaust.

Of course, parents deserve a say in the materials used to teach their children, and in the U.S., local communities are in charge of which books are taught in public schools, and which are not permitted.

But in 2022, eighth graders in even the most socially conservative communities are almost certainly exposed on a daily basis to far more lascivious sexual imagery on TikTok and YouTube than exists in Maus. And if violent or disturbing imagery is too much for 13 and 14-year-olds, it’s hard to imagine any book about the Holocaust would be deemed appropriate.

The fact is, everyone should read Maus—and middle school actually seems like the perfect age to do so.

The New York Times’ Jane Coaston put it eloquently in a Twitter thread:

“I read "Maus" when I was nine years old and it changed my life. It made me a better person, a more empathetic and compassionate person. I think "Maus" should be as widely read as possible.”

When access to great books is squelched because of the myopic hyper-moralism of the local community—it’s a loss for the kids. And that’s the case whether it’s social conservatives afraid their children might see a pencil-drawn boob or progressives shielding young people from books set in decades (or centuries) past, which include some characters speaking in the racist and otherwise ignorant vernacular of their eras.

A small school district removing Maus from its curriculum shouldn’t be oversold as a harbinger of Third Reich book burning, but neither should it be brushed aside as a “manufactured outrage.” And yes, we in the media should be precise with our words—and promiscuously using the word “ban” is bound to needlessly confuse the issue.

What’s legitimately disheartening is that Americans of various political stripes remain so quick to bury (if not ban) books that confront humanity’s worst instincts, as if knowledge, rather than ignorance, is more likely to cause children harm.

Particularly in a country that prides itself on its robust tradition of free expression and defending the right to make others uncomfortable, we’d all be better off if our kids more regularly engaged in challenging material.

Art that doesn’t make its audience at least a little uncomfortable is just disposable entertainment. Only when you’re removed from your comfort zone is meaningful change possible.

Maus is such a work of art. Everyone should read it, especially middle-schoolers.